Making your tucker on the wallaby is an exercise in minimalist food preparation and cooking. Sure, you can take modern pre-prepared or freeze dried foods with you instead of the stuff the old-timers carried, but between you and me… that’s cheating. Taking a gas cooker or even an alcohol stove is cheating too. If the bushfire fire danger allows it, you use an open fire for your cooking. If it doesn’t then stay home or “cheat” and use a Jetboil and freeze dried slop-in-a-bag.

You’ll find that the “minimalist” concept I’m talking about relates mostly to your cooking equipment. There’s no cast ironware, enamel boilers or fold up grills here. Since you’re carrying it all in your nosebag, you want your cooking equipment to be as light as possible while still being effective.

The cooking gear described in this post is more of a Queensland style used by swagmen travelling that great state. It’s traditional, but there are many other options for preparing your tucker as the swaggies did. You can read more on this in my soon-to-be-released book On the Wallaby Track: A Swagman’s Handbook.

Something to boil water in

For the purposes of this post, we’re boiling in a quartpot. Traditionally, a quartpot was a small billycan with a pannikin (cup) stuck inside. Made from tinplated sheet metal or from copper, the quartpot was a very common piece of equipment for the bushman, whether he was a swaggie, drover or prospector. The quartpot even pre-dates the billycan by about 40 years. You can see references to them in books and newspaper articles circa 1810s since an earlier, but very similar design were issued to convicts as a type of mess tin. They are still in use by stockmen today, as well as by some of us who like to bushwalk and camp in the old style since they are twice as useful as a billycan.

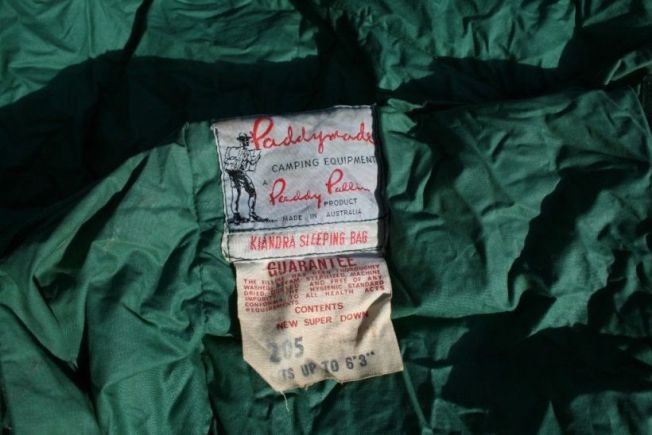

Some of my quartpots – from left – Stainless steel oval section quartpot and pannikin made by Ord River, John Williams Beltana pattern round pot and pannikin, vintage station-made round pot and pannikin – made from kerosene tin sheet metal and fencing wire.

My own quartpot and pannikin were sold by RM Williams and were made by RM Williams’ son, John. They seem to have gone out of production sometime in the last 12 months, but hopefully they’ll be back. The type of quartpot and pannikin I use are a round type. You can find quartpots with a “D” profile or oval or rounded rectangular profiles. These are stockman’s patterns designed so they don’t stick out too far when strapped to the side of the saddle.

In use, a quartpot has to be filled to the brim to stop the solder from being burnt out. It is pushed into the side of the fire, downwind of any prevailing breeze so that the flames lap around the whole pot, making it boil quicker. The oval profile quartpots excel here since the surface area is greater they tend to boil quicker.

If water is at a premium, you can boil water in the pannikin itself. As with the quartpot, you need to make sure the pannikin is filled to the brim or you’ll ruin it.

You wouldn’t try to make a stew in a quartpot, but it’s quite OK to use it to brew up tea or coffee. A burnt-on stew is a bit harder to clean up than coffee grounds or used tea leaves.

Something to fry on

Frying an egg is a challenge unless you have some sort of hotplate or frypan. You don’t want to carry a frypan but since you have a tin plate, it can be heated up on the fire and will become a… hotplate.

I usually drill a couple of holes near the edge of my plate when I want to take it off the fire, I’ll simply hook it with a piece of bent wire and drag it out.

Eggs aren’t the only thing fried on a hot plate. Johnnycakes and even corncakes come up beautifully when fried. As does bacon or slices of corned beef. To flip your tucker while you’re frying it you need some utensils. I have made simple tongs out of fencing wire and a lightweight, but effective spatula out of a flattened corned beef tin and a length of deadfall timber secured to it with wire.

Something to grill on

You can of course make your own campfire grill out of some bendy green sticks, but if you do, you’re a vandal. You see, they only last for one use so you’ll have to make up a new one every time you want to grill a bit of meat or apple as you as go along, killing a bunch of saplings or stripping live branches in the process. Nope, in today’s environment you need to make up one which lasts, and which you can rely on even if there’s not a green stick to be found.

The traditional swagman’s solution was a bit of fencing wire bent up into the shape of the swagman’s hand. When not in use it was folded up and slid down inside the nosebag. It weighs very little and is highly effective. I’ve cooked bacon on one, grilled sausages, bits of steak, slices of apple and have toasted up pre-cooked johnnycakes on one.

Something to make damper in

You don’t really want to carry around a big mixing bowl and unless you have tons of water available, mixing damper in your quartpot or billy will lead to a huge mess. The swaggies mixed their damper on a bit of cloth laid over a depression they kicked into the dirt.

The well-equipped swagman used a square of canvas brought along specially for the purpose, but everyone else used the back of their coat or even the underside of their canvas swag cover. Some even used a wool blanket. If you first put down a lot of flour you don’t get much dough sticking to the mixing sheet. When it’s dry it can be blown or scratched off anyway.

I tend to use a square of calico myself.

Cooking Damper and Johnnycakes

Damper is best cooked directly on the coals or in the ashes of the fire. You’ll find that the ash and coals don’t stick and can be brushed off easily. With the sand method described below, the sand brushes off easily too. Cooking them this way is nowhere near as bad as it sounds. The secret is to coat the uncooked dough with a layer of dry flour.

Johnnycake cooking directly on the coals.

For the best damper, it’s actually best to cook it in hot sand. Make a depression in the sand and light a fire which burns down to a nice hot bed of coals. Brush aside the coals and lay the damper on the hot sand underneath. Brush the coals back over the damper and then bury the whole lot in sand. Mark your damper with a stick so you don’t lose it.

After the damper has cooked you need to completely cool down the hot sand with copius amounts of water before you move on. If any person, stock or native animals walk over the hot oven they can be seriously injured. Don’t leave it until you’d happily walk on the dug up damper hole with bare feet.

How do you know when your damper is done? You stick in a twig or your knife blade. If it comes out clean then the damper is cooked. If it has dough on it, then leave the damper in for another half an hour.

Johnnycakes can be cooked in exactly the same way as dampers, but I find I prefer to cook them on the tin plate over a medium-hot fire. You can cook a bunch of them at a time and the process is just more controllable.

Something to cut on and with

To cut up cheese or corned beef or pork belly or vegetables, I just tend to use the tin plate. You can carry a plank of wood around as a chopping board or you can carve one from a bit of deadfall timber on site. The best improvised cutting board I have found is a coolamon made from a sheet of bark from an old flood-felled sheoak (casuarina) tree. Works great

The most important cooking utensil is a knife. I carry a sharpened vintage butter knife which sees more use as a food chopper and slicer utensil than anything else.

I haven’t covered any food hygiene here. More on that in a later post.

You must be logged in to post a comment.