Through my recent eBay adventures, my vintage compass collection has increased dramatically. Some of my favourite new acquisitions are a pair of 1918-vintage US Corps of Engineers military marching compasses both made by Cruchon & Emons in Switzerland. These are the types of compasses that Horace Kephart might have used.

Left: US Corps of Engineers Verner’s Pattern Mk. VIII prismatic marching compass. Right: US Corps of Engineers mirror sighting compass.

The Verner’s Pattern Mk. VIII Prismatic Marching Compass

Signed “C-E” for Cruchon & Emons (NOT “Corps of Engineers” as you would expect), the 1918-dated Verner’s Pattern Mk. VIII prismatic was an absolute basket case when I purchased it. Incomplete, and with a heavy layer of dirt, staining and filth (inside and out) it looked like it had lain in a swamp for 50 years. A trip to a local hobby store saw me secure some brass bar for the replacement lid-opening tab and an assortment of correct-size replacement slot head brass screws.

Despite the complexity of the design, which includes both a dial-locking mechanism as well as a manual dial-damping button, the teardown for cleaning wasn’t difficult and only took about five minutes.

The inside of the case under the dial was absolutely filthy – it went WAY beyond patina. After cleaning all the brass parts and giving them a mild polish with Brasso, the compass began to look great. Internal parts such as screw threads and the dial jewel were lubricated with pencil graphite and the missing parts fabricated and fitted until I can secure a junked case from which to cannibalise those parts.

Having polished the lid, it was hit with a light coat of black lacquer to imitate the brass blacking (an actual oxidization process) used on the compasses at the Swiss factory in 1918. You can see some strong remains of the original blacking on the mirror-sighting compass below.

Due to the potential radiation hazard from the remains of the radium illumination on this compass, all cleaning and restoration work was carried out while wearing a military-grade S10 respirator and surgical gloves.

It’s worth noting that the Verner’s Pattern Mk. VIII compass was the standard British Commonwealth field compass for most of the First World War. British-marked wartime examples are common, but the US-marked ones less so due to America’s later entry into that conflict.

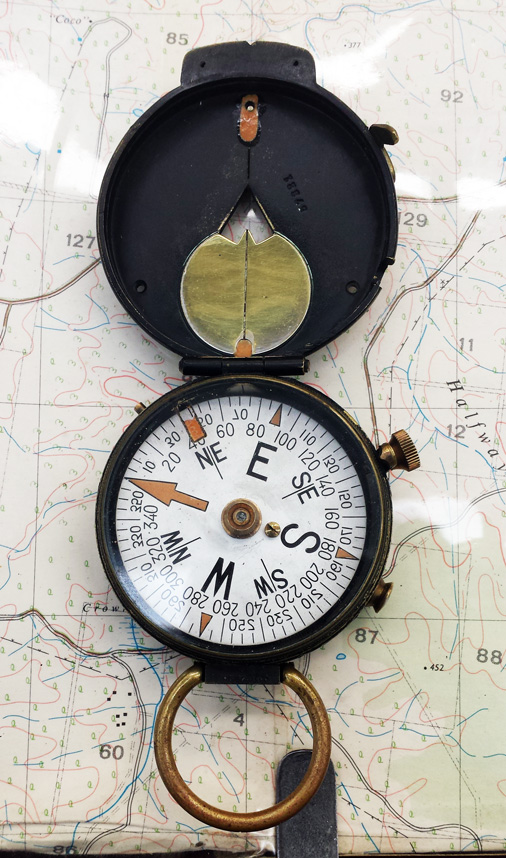

Cruchon & Emons Mirror Sighting Compass

This compass operates in a similar fashion to modern mirror-sighting baseplate compasses. One ring of indices on the dial is printed back-to-front and mirrored. To take a bearing, the user reads the mirrored bearing off the highly polished brass plate set into the lid.

The Cruchon & Emons mirror sighting compass. Note the highly-polished brass mirror which was the beating heart of this system.

Manufactured in Paris, France and in Berne, Switzerland by both Plan Ltd and Cruchon & Emons from 1915, the mirror sighting compass was never as well-regarded as the prismatic models. When introduced into US Army service in 1916, this mirror sighting compass was the most accurate marching compass ever fielded by US forces.

This example is a Berne-manufactured compass which dates to mid-late 1918. Although there are no date stamps, we can narrow it down due to the use of an aluminium dial (until mid 1918 they were enameled) and the brass mirror (brass mirrors were phased out in late 1918 and replaced by nickel-plated mirrors which wouldn’t tarnish under field conditions).

Like the Verner’s Pattern prismatic above, the compass is still highly accurate down to about half a degree when compared against a 1943 MkIII Marching Compass and a 2000s Silva 4/54 military baseplate compass

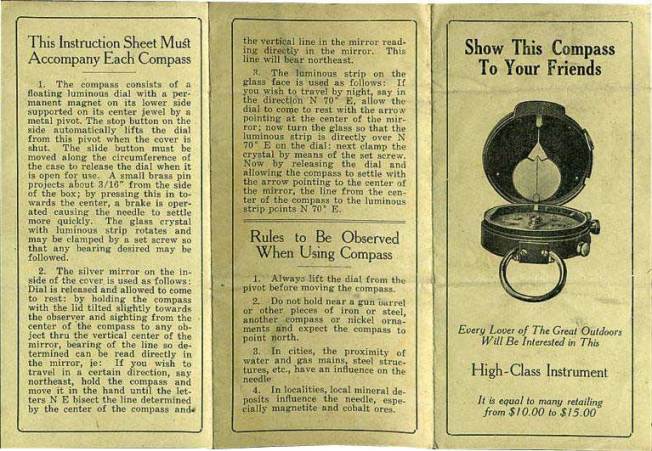

Instructions for use of the mirror-sighting compass. Image courtesy www.compassmuseum.com

Despite the failure of any of the major militaries of the world to adopt the mirror sighting compass as standard (the US standardised on the Verner’s pattern prismatic compasses after WWI before adopting the lensatic pattern in the 1930s), the mirror sighting compass became a favourite amongst outdoor enthusiasts and wilderness travellers – particularly in North America. In the 1920s and 30s, outdoors outfitters Abercrombie & Fitch retailed a very similar compass, also made by Cruchon & Emons, proving that the type’s popularity as a general purpose direction-finding instrument did not wane for decades.

With index marks on the thumb-ring, the sighting window and the top of the lid, the mirror sighting compass is well-suited to field navigation with a map – of course, you do need a protractor to navigate effectively.

A Photo Comparison of the 1918 Verner’s Pattern Mk. VIII Prismatic Compass and the 1943 Mk. III Prismatic Compass

Sometimes it’s interesting to see the evolution of pieces of equipment over the years. Both the compasses shown below were state of the art for their day.

The 1918-vintage Verner’s Pattern (left) with polished case and blackened lid. the 1943-vintage GEC Mk. III prismatic compass (r) is in mint restored condition – all radium removed and replaced with Tritium and a mint-condition black lacquered case.

The Verner’s Pattern is a “dry card” type which means it can take a while for the north indicator to settle and give an accurate reading. Dial movement can be arrested by a damping button, which slows the movement without affecting accuracy. When the case closes, a tab on the lid engages a mechanism in the case which lifts and locks the dial to protect it from shock and damage.

The Mk.III prismatic has a liquid-filled capsule within which the dial card can move freely, but provides effective damping for quick readings when time is of the essence. As you can see from the photos, the beefy Mk.III is a monster when compared to the fine-featured Verner’s Pattern

Aside from the dissimilar damping mechanisms and the indexed rotating ring on the Mk. III, the basic theory of operation for both compasses is almost identical.

The compass bases. The fibre friction ring is missing from the Verner’s Pattern. Note the data on the GEC Mk.III – The “B” prefix on the serial number indicates this compass was manufactured by Francis Barker & Sons, while the lack of a date mark indicates it was one of a small batch of undated examples manufactured by F Barker & Sons in 1943 – a rare bird.

Those are beautiful works of art.

Most excellent and good work. Thanks for sharing

Thanks guys.

I have the Engineer Corps compass on the left images.

Is there a place I can get a value for it? And is there a collectors sight, I’m interested in selling it.

Hi, there are a bunch of collector sites out there such as http://compassmuseum.com/ and http://www.scientificcollectables.com/page_compasses.htm

Check ebay completed listings for what a similar compass might have sold for.

Great articles Craig! We have a small collection of 50 to 60 British, Australian, US and German WWI & WWII compasses, including a couple of really nice sun compasses, and it’s nice to see the subject getting some attention.

Thanks Al,

That’s a nicely sized collection! Including escape compasses I probably only own 8 or 9 vintage compasses.

What model sun compasses do you have? I find them fascinating.

Cheers!

Hi there, interesting read. I have my great-grandad’s Verner Pattern VIII and was interested in restoring it, but the radium thing got me spooked. I’ve not taken/figured out how take off the inner lid, i’m guessing handling with it on is still safe? and what did you use to clean the brass. Also, how come the top half is darker? Thanks

Thomas,

Unlike the later WWII era liquid damped compasses which get bubbles and evaporation of the purified kerosene damping fluid, an air-damped Verner’s Pattern prismatic like your great-granddad’s will work fine for another hundred or so years as long as there’s no corrosion inside the compass itself.

Radium is definitely an issue, so if the compass dial moves the way it should then I’d suggest just leaving it alone. It’s quite safe to handle as long as it’s all sealed up.

I used a heady mixture of Brasso and elbow grease to clean the brass.

The top half of the compass was blackened for three reasons:

1. to stop the flipped open compass lid acting as a shiny aiming point for enemy snipers;

2. to stop the reflections from a highly polished compass lid dazzling the user while taking a bearing in bright sinlight;

3. The blacking on the lid protected the brass finish and kept the military spit-and-polish brigade happy.

Incidentally, since I wrote the article above, I’ve sold the US Army Verner’s Pattern VIII and replaced it with a Swiss manufactured, British Broadarrow-marked Verner’s Pattern VIII in almost perfect condition along with leather Sam Browne case, etc. I note with interest that the “new” Verner’s Pattern compass has had all of the bright brasswork hit with clear lacquer at the factory to protect the finish. So a properly restored compass should have the polished brasswork on the case clear-lacquered and the lid and lifting tab black lacquered or otherwise oxidised with a brown/black finish.

I hope it helps.

That is really helpful, thanks. So really there’s nothing stopping me from giving it a good clean then top and bottom! My relative kept it in his dank cottage full of damp so the leather case is on it’s last legs. The top lid glass is cracked as well, which I can’t do much about. Thanks again!

What a fantastic site. I’ve got a Verners MkVIII that needs some work – the card doesn’t rotate

and yes I’ve taken the transit lock off 🙂 Can you point me to a resource for stripping down these compasses? I don’t want to start attacking screws without a guide! Thanks also for the pointers about protective gear.

Hi Colin, I can’t recommend that you disassemble the compass due to the risk posed by the radium, but I will say that as per the image in the post, it’s a pretty simple process, even for the uninitiated and I didn’t have a guide. I daresay yours might have some corrosion or gunk on the pivot, or perhaps the brake is engaged? If the transit lock is disengaged, there’s not much else it can be if the compass looks undamaged externally. I’d try first lubricating the brake button and making sure it moves in and out. If this doesn’t free up the card, then you might have to take the risk and go in after it man-to-man. Good luck.

Hi Craig, You have a fascinating site which I came across as I researched the date of a marching compass that has come into my possession. It turns out that it is in fact an exact copy of the Mk111 you have here. Its serial number is 141312 which I imagine makes it slightly earlier than your example but it is in fine original condition no doubt because it has bee stored in a rather nice velvet lined leather case. The top dial? is a little stiff due to lack of use I think but the compass works fine. I don’t think I’ll be keeping it as it has no apparent link to my family so would appreciate any advice as to how best to sell it and what I should be asking. Many thanks Mike

Hi Mike, I’d have to see the compass (and case) to be able to give an accurate appraisal, but generally you can expect to sell a good, functional MkIII between US$100 and maybe even up to US$250 if it’s in perfect condition, particularly if the leather Sam Browne case is present and also in good, serviceable condition. Try selling on ebay, etsy or on the Facebook marketplace if you frequent social media. Cheers, Craig.

Hello Graig. A simple question for you. Can you please explain how to disassemble the glass and the rose of the Verner’s Pattern VIII COMPASS ?. I’m going to buy one of them that needs to be cleaned and lubrificated. Thank you.

Hi Craig, I have a Vernier Patern VIII. Can you tell me how I should replace the friction ring on the back of it It also has an imprint of A E with an arrow between them. It has no other markings. What do you think this means.

Hi Ken, I have no idea what “AE” with an arrow might mean. I have seen “AF” which is a WWII Royal Australian Air Force marking or “AM” which is a British Royal Air Force Marking. Maybe ask on a militaria forum where you can show pictures of your compass? You can find friction rings in new or at least unissued condition which were made for the post-War MkIII, MK3A, M73 and M88 prismatic compasses. You would need to find someone selling one then see if the dimensions are the same for your Verner’s Pattern VIII.

Hi Craig, Thank you for a terrific site. I have a Plan mirror compass (sn 63346) that appears to be in decent shape and has some family significance. I would like to clean it up (save the patina!) and get it into working order, which would include freeing the glass crystal which no longer rotates. I’d greatly appreciate any disassembly hints and cautions you might be able to offer.